chapter

3

initial assessment: republic of india

Executive Summary

The Internet infrastructure in India today is poor. Although the number of users is relatively low, they already overwhelm the network’s capacity. The dimensions of the Internet in India are provided in Table 10 and Figure 1. Government policies and inaction have been the principal causes of the Internet’s lack of development in India, compounded by the country’s poverty and the attendant extremely poor telecommunications infrastructure. Privatization of the telecommunications sector has begun, but noticeable improvements in basic telecommunications (e.g., the quality

|

Dimension |

Level |

Explanation |

|

Pervasiveness |

(1) Experimental |

The Internet user community comprises less than 1 person in 1,000. However, the user community extends well beyond a core of networking professionals, and there are hundreds of computers connected to the international Internet. This dimension will likely increase to 2 by 1999. |

|

Geographic Dispersion |

(2) Moderately Dispersed |

Internet points of presence are currently located in 14 of 25 States and 3 of the seven Union Territories (17 of 32 first-tier administrative divisions). Planned near-term expansion will connect three more States. There are international connections from at least 12 locations, six of which serve the public network. |

|

Sectoral Absorption |

(1) Rare |

There is leased-line connectivity to the Internet in less than 10 percent of the constituents of every sector. |

|

Connectivity Infrastructure |

(2) |

The average bandwidth of the domestic infrastructure is less than E-1 (2.048 Mbps). There are several closed and bilateral Internet exchanges. Access is predominantly via modem, but 64 Kbps leased lines are available and used. |

|

Organizational Infrastructure |

(2) Controlled |

There is only one commercial Internet service provider (ISP) offering public Internet access. The legal barriers to establishing new ISPs have been eased, although the degree of competition that will be allowed remains unclear. |

|

Sophistication of Use |

(2) Conventional |

The Internet is being used to improve the efficiency and expand the scope of current activities and processes without fundamentally changing them. |

|

Table 10. Internet Dimensions for India |

||

and availability of local loop, inter-exchange, and long distance connections) will take several years to achieve, even in the absence of any further government interference.

Figure 1. Indian Internet Dimensions, 1988-1998

The development of the Internet in India has occurred in three phases: a promising beginning in the 1980s, a lengthy period of stagnation, and the current phase that promises rapid future growth. The academic community was the first to use the Internet and was responsible for its introduction into India. This is consistent with the “early” model of Internet diffusion. However, from its introduction until the present, the Internet has seen little development. Future growth of the network will be driven by commercial forces and requirements, consistent with the “later” model of Internet diffusion.

· Promising Beginning The first Internet connection to India was effected in 1989.

· Interest in the Internet resulted in government action in 1986, with the establishment of the Education and Research Network (ERNET) as a project within the Department of Electronics (DoE). At this early date, the government telecommunications agencies had no interest in what was viewed as a non-standard network protocol with no commercial applications.

· Coincident with the beginning of ERNET, the DoE established the Software Technology Parks of India (STPI) as incubators for small software development companies in an effort to spur the export of software.

· Following this early recognition of the Internet as a potentially useful tool for the academic community, nearly three years elapsed before the first connection to the Internet was made. The National Centre for Software Technology (NCST) brought the ERNET on-line in 1989, followed shortly thereafter by STPI.

· Stagnation From 1989 through 1995, there was hardly any further growth of the Internet.

· The DoE did not have adequate funding to proliferate the ERNET throughout the academic and research communities. As a result, the ERNET grew only very slowly and only as a result of direct efforts by institutions that wished to be connected. Eventually, 700 organizations were connected, but use and bandwidth continue to be limited.

· Although STPI established a satellite communications network connecting the member parks and companies with each other and clients overseas, this network was and continues to be used principally for point-to-point communications between individual companies and their clients. SoftNet has offered Internet links for almost a decade, but the system remains under-utilized.

· The government telecommunications monopolies, the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) and Mahanagar Telephone Company Limited (MTNL) for domestic communications and Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited (VSNL) for international communications, continued to refuse to consider implementing TCP/IP networking. Such efforts as were expended on developing data networks focused on accepted international standards such as X.25 and X.400.

· Poised for Growth? Commercial Internet connections became available in India in 1995.

· VSNL established the first commercial Internet links as a “gateway” service in August 1995, adding it to its portfolio of international telecommunications services. Additional nodes for local access were built by VSNL and turned over to the DoT for operation.

· Despite the demand for services, however, the prices remained high for several years, and access was limited by the small number of hosts and limited number of dial-up lines. Between 1995 and early 1998, only 30 nodes, connected to the Internet through six international satellite gateways each with limited bandwidth, were built. There were only about 150,000 subscribers—about 0.01 percent of the population—by mid-1998, fully half of whom had only signed up for service following a significant price reduction in January 1998.

· Government and court decisions announced in June and July of 1998 have cleared the way, at least in principal, for the licensing of an unlimited number of private ISPs, which will also be allowed to establish international links to the Internet independent of the government monopolies. This freeing of the market is expected to result in a large infusion of investment and the rapid creation of multiple, competing services.

· The basic telecommunications infrastructure is also expected to improve, albeit more slowly, as the sector is opened to competition and new providers bring their networks on-line. The Indian railroads and electrical power companies (themselves government monopolies) are already installing new fiber optic networks along their respective rights of way.

There is a high demand for Internet services, especially in the private sector. Public-sector undertakings have made some efforts, albeit with only limited success, to meet this demand. Recognizing its inability to provide the capital investment required for rapid network expansion, and in keeping with the general trend of privatization of the telecommunications sector, the Indian government decided to open Internet service provision to the private sector. Bureaucratic “turf battles” between incumbent public-sector operators and the newly-created independent regulatory authority have resulted in a delay of about one year in the licensing of private Internet service providers. Licensing should begin in the fourth quarter of 1998 and the first private commercial service providers could be offering Internet access in early 1999.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which took over as the leading party in the Indian government earlier this year, identified information technology (IT), especially software exports, as key to the country’s future economic growth and development. In keeping with the priority that its party platform placed on IT, the BJP government appointed a blue-ribbon National Task Force on Information Technology and Software Development to identify the relevant goals and the means for achieving them. In the IT Action Plan produced by the Task Force (included at Tab C), the further diffusion of the Internet was explicitly identified as important for the country’s future. Specific recommendations included requirements to provide Internet connections in every district, school, and medical establishment.

The IT Action Plan was approved by the Indian Parliament in July 1998, and now has the force of law. This means that every ministry and department of the Indian government has been tasked to issue or amend the required laws and regulations to implement the Action Plan’s recommendations. The next step, identifying the specific steps to be taken within the Indian government to implement the various recommendations, is underway. There are early indications that the recommendations that require legislative action, such as changes in import and export regulations, will be implemented by the Parliament. Whether the vast Indian bureaucracy will respond to the bulk of the recommendations, however, is far from certain. The most significant shortfall is the lack of identified budget resources to support implementation of the Action Plan. The National Task Force evidently has placed a great deal of confidence in the private sector’s ability and willingness to invest in the country’s infrastructure and the further development of the IT sector. Citizen participation is critical as well, since the potential for successful private sector initiatives relies to a great extent on the Indian consumer.

Government inactivity has been largely responsible for the slow pace of Internet development in India to date. The adoption of the IT Action Plan signals the Indian government’s recognition that the country is at a strategic crossroads, where is must chose whether to continue business as usual and continue to fall behind not only the developed world but its own neighbors or overhaul the government bureaucracy to more effectively develop and employ the country’s vast human resources. Attempts to realize the Action Plan’s ambitious program will have a salutary effect on the availability and use of the Internet in India. The further development of the Internet will, in turn, contribute to the success of the Action Plan. However, even should the Action Plan be entirely or largely scrapped, unlikely in our judgment, the current regulatory and commercial environments will ensure that the Internet continues to grow in India, albeit at a slower pace and less widely than it would have with the support of the Action Plan’s initiatives.

In this final quarter of 1998, the Internet in India is beginning to show some robust growth, and the situation is such that it is poised for exceptionally rapid growth over the next twelve months, should the government do its part. With the recent decisions and court rulings that have opened the way for private Internet services providers to compete with the public sector operators, the prospects for competition are good. The government must come through, however, with the promised ISP licenses, and the defense ministry must approve the ISPs’ international connections. Legislative action is required to authorize competition among domestic backbone providers. To ensure that the full potential of the Internet is realized, the government must make at least a good-faith effort to implement the Action Plan. This will require not only the issuance or amendment of laws and regulations, no simple task in itself, but the enumeration of specific steps and processes to implement the Action Plan’s recommendations. The bureaucracy must be tamed, as well. Most importantly, where the government cannot directly fund recommended projects, and this includes most of the Plan’s recommendations, the promise of incentives to lure private sector investment must be fulfilled. These requirements, however, strike at the heart of any bureaucracy’s core values: its own processes and its revenues, both of which it seeks to maintain and increase as a matter of course. As was recently noted in the Indian press, “it’s an expensive business keeping the Indians in poverty.”[8]

The government of India has recognized that the country requires a “jump start.” The lessons of the recent problems with privatization, such as the extensive litigation and loss of international capital investment in the basic telecommunications circles and mobile telephone projects, suggest that the government must more carefully plan its projects and be much more consistent in their implementation, especially with respect to the lessening of the government’s direct role. The government appears to recognize these lessons, and may even have taken them to heart. A critical mass may have been reached. IT is developing ever more quickly and “information content” of all products is rapidly increasing. Despite impressive achievements, Indian IT has largely been stagnating. With business as usual thoroughly discredited, the government’s actions during the next year will likely determine whether India enters the 21st century in the vanguard or bringing up the rear.

A cautionary note Despite all the favorable portents, there is still a significant possibility that the bureaucracy will, if not stifle, at least stall or weaken future development. As N. Vittal, former Secretary of Telecommunications and a member of the National Task Force, reminds us: “Don’t underestimate the power of the babus. An army marches on its stomach. But the government marches on paper.”[9]

Introduction

The “largest democracy in the world,” India is the world’s second most-populous nation, although it is only about one-third the size of the United States. The country’s population of more than 960 million people (Table 11) comprises two major ethnic groups, Indo-Aryan and Dravidian, speaking 15 official and dozens of unofficial languages, which are approximately as mutually intelligible as those in Europe and are not written using the Latin or other common alphabet. English is thus the language of inter-communal business and much of the central (Union) government’s operations, as well as of the judicial system. As one Mumbai (Bombay) resident mildly exaggerated, “India has 980 million people and even more gods. Travel 30 or 40 kilometers, and everything changes: people, climate, culture, geography, food, religion.”

|

Table

11. India in Statistics |

||

|

Metric |

Value[10] |

Remarks |

|

Population |

944.58 966.78[11] |

millions, 1996 millions, July 1997 estimate |

|

Population density |

298 |

per km2, 1996 |

|

GDP |

338.8 |

US$billions, 1995 |

|

GDP per capita |

365 |

US$, 1995 |

|

Telephones |

14,542.7 |

thousands, 1996 |

|

Teledensity |

1.54 |

telephones per 100 inhabitants, 1996 |

|

Teledensity in largest city |

11.3 |

telephones per 100 inhabitants, 1996 |

|

Cellular subscribers |

328.0 |

thousands, 1996 |

|

Cellular density |

0.03 |

cellular lines per 100 inhabitants, 1996 |

|

Personal computers (PC) |

1,400 |

thousands, 1996 estimate |

|

PC density |

0.15 |

PCs per 100 inhabitants, 1996 estimate |

|

Television sets (receivers) |

60,000 |

thousands, 1996 |

|

Television set density |

6.4 |

TVs per 100 inhabitants, 1996 |

|

Literacy rate |

52[12] |

% of population >14 years old, 1997 est. |

|

Infant mortality |

65.5[13] |

deaths per 1000 live births, 1997 est. |

From the first known settlements around the 24th century B.C., through the middle of this century, the Indian subcontinent has been subjected to five major invasions from the north and west, three of which resulted in the establishment of foreign rule over much of the region. Also, during the height of European exploration in the 16th century, relatively small sections of the country were acquired by several European powers. Today’s India still shows the effects of Mogul rule in its most famous tourist sites and lingering divisions between Muslims and Hindus, and the effects of more than a century and a half of British rule, most especially in the extensive government bureaucracy and common use of the English language. Portuguese can still be heard in the former colony of Goa, while French is common in the villages of the Pondicherry enclaves.

The modern Republic of India was created in August 1947, when the British granted its former colony its independence, at the same time separately creating the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in the northwestern and northeastern regions of the colony. The ensuing flight of Hindus from Pakistan and Muslims from India resulted in a population exchange of about 10 million people and a huge death toll from inter-ethnic violence. India has since fought two wars with Pakistan, the most recent of which resulted in the secession of East Pakistan as Bangladesh. The northern border region between India and Pakistan, Kashmir, is still contested between the two countries and is the locus of continued military deployments and sporadic armed conflict. India also fought a border war with the People’s Republic of China in the Arunchal Pradesh, the border of which is still disputed. Thus, almost half of India’s land borders abut hostile neighbors.

The Indian subcontinent is a 3.3 million km2

diamond that dominates the Indian Ocean, with 7,000 km of coasts on the Indian

Ocean, North Arabian Sea, and Bay of Bengal (Figure 2). The extent of the

modern republic, with the exception of the Northeastern Region, is naturally

bounded by these coasts and the mountains to the northeast and northwest.

Within its borders, virtually every type of climatic and geological region can

be found. The Vindhya and Satpura mountain ranges of central India, just north

of the Tropic of Cancer, have historically impeded north-south communication,

reflected in the virtually independent development of empires and cultures in

northern and southern India.[14]

The country is divided into 25 states and seven Union territories that are

administered by the central government, listed in Table 12.

The Indian subcontinent is a 3.3 million km2

diamond that dominates the Indian Ocean, with 7,000 km of coasts on the Indian

Ocean, North Arabian Sea, and Bay of Bengal (Figure 2). The extent of the

modern republic, with the exception of the Northeastern Region, is naturally

bounded by these coasts and the mountains to the northeast and northwest.

Within its borders, virtually every type of climatic and geological region can

be found. The Vindhya and Satpura mountain ranges of central India, just north

of the Tropic of Cancer, have historically impeded north-south communication,

reflected in the virtually independent development of empires and cultures in

northern and southern India.[14]

The country is divided into 25 states and seven Union territories that are

administered by the central government, listed in Table 12.

Despite the large populations and attendant high population density, India remains a largely rural country, with about 70 percent of the population residing outside of the major metropolitan areas. About 67 percent of the work force is employed in the agricultural sector.[15] The varying geological and climatic conditions and the dispersion of the country’s vast population make the development and maintenance of basic infrastructure components (e.g., roads, electrical power distribution, telecommunications) difficult and expensive. The poor infrastructure and population density and dispersion compound the problems caused by frequent natural disasters such as flooding and earthquakes.

Key

Organizations

Department of Telecommunications (DoT)—The DoT (which does not have a Web site or home page) is subordinate to the Ministry of Communications and was until recently the monopoly domestic telecommunications service provider, except in Mumbai and New Delhi. The provision of local telecommunications services has been liberalized, with commercial groups now licensed to provide service in 20 regional “circles.” DoT remains the monopoly provider of long distance (i.e., inter-“circle”) telecommunications. DoT operates the domestic terrestrial IP infrastructure and offers Internet service to the public in conjunction with VSNL.

|

Table 12. Indian States and Union Territories |

|||

|

State |

Capital |

State or Union Territory* |

Capital |

|

Andhra Pradesh |

Hyderabad |

Nagaland |

Kohima |

|

Arunachal Pradesh |

Itanagar |

Orissa |

Bhubaneshwar |

|

Assam |

Guwahati |

Punjab |

Chandigarh |

|

Bihar |

Patna |

Rajasthan |

Jaipur |

|

Goa |

Panaji |

Sikkim |

Gangtok |

|

Gujarat |

Gandhinagar |

Tamil Nadu |

Chennai (Madras) |

|

Haryana |

Chandigarh |

Tripura |

Agartala |

|

Himachal Pradesh |

Shimla |

Uttar Pradesh |

Lucknow |

|

Jammu and Kashmir |

Srinagar |

West Bengal |

Calcutta |

|

Karnataka |

Bangalore |

Andaman and Nicobar Islands* |

Port Blair |

|

Kerala |

Trivandrum |

Chandigarh* |

(metropolitan region) |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

Bhopal |

Dadra and Nagar Haveli* |

(cities) |

|

Maharashtra |

Mumbai (Bombay) |

Daman and Diu* |

(cities) |

|

Manipur |

Imphal |

Delhi* |

(metropolitan region) |

|

Meghalaya |

Shillong |

Lakshadweep* |

Kavaratti |

|

Mizoram |

Aizawl |

Pondicherry* |

Pondicherry |

ERNET India—An autonomous society,

ERNET India (www.doe.ernet.in) was established in 1998 under the Department of

Electronics (DoE) to assume the task of operating, maintaining, and further

developing the Education and Research Network, which was established by the

Information Infrastructure Division of the DoE in 1986. ERNET India operates an

IP network and offers Internet connectivity via VSNL to member organizations

from the academic and research sectors.

ERNET India—An autonomous society,

ERNET India (www.doe.ernet.in) was established in 1998 under the Department of

Electronics (DoE) to assume the task of operating, maintaining, and further

developing the Education and Research Network, which was established by the

Information Infrastructure Division of the DoE in 1986. ERNET India operates an

IP network and offers Internet connectivity via VSNL to member organizations

from the academic and research sectors.

Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. (MTNL)—Literally, the “Great Cities” telephone company, MTNL (www.nic.in/mtnl) was established on 1 April 1986 to provide local telecommunications services in Mumbai and New Delhi. MTNL is a public sector company subordinate to the Telecom Commission under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Communications; however, 20 percent of the stock was listed on public stock exchanges during 1991-92. MTNL has applied for a license to become an Internet service provider (ISP).

National

Centre for Software Technology (NCST)—The NCST (www.ncst.ernet.in) is a

DoE research center in a northern suburb of Mumbai. It was the first ERNET

member organization to establish an international connection to the Internet,

and is the .in national top-level

domain (TLD) manager (i.e., NCST is the registrar for the .in TLD).

National

Centre for Software Technology (NCST)—The NCST (www.ncst.ernet.in) is a

DoE research center in a northern suburb of Mumbai. It was the first ERNET

member organization to establish an international connection to the Internet,

and is the .in national top-level

domain (TLD) manager (i.e., NCST is the registrar for the .in TLD).

National Informatics Centre (NIC)—The NIC (www.nic.in) was established in 1975 by the Planning Commission to act as a centralized source of information and services for the government. It has since extended its coverage to include state and district governments and public sector companies and societies. The NIC also provides computer training and consulting services, and develops software for government applications. The center’s nationwide computer network, NICNET (www.nic.in/nicnet.html), is one of the largest very small aperture terminal (VSAT) networks in the world, offering X.25 and IP packet switched communications, with a gateway to the Internet via VSNL.

Software Technology Parks of India

(STPI)—STPI (www.stpi.soft.net), another DoE autonomous society, was

established in 1986 as part of a concentrated effort to boost export earnings

from software development and related professional services. These parks offer

a full-service “incubator” environment for entrepreneurs and small companies.

Services offered include office spaces at affordable rates, equipped with

stable electrical power supplies and international communications links. STPI

also offers a wide variety of business services and acts as a single point of

contact for companies dealing with the government. The concept was the

brainchild of Dr. N. Sheshagiri, Director-General of the National Informatics

Center, and N. Vittal, at that time the Secretary of the DoE, both of whom

serve on the National Task Force on Information Technology and Software

Development, the current effort to boost the IT sector once again.[16]

Software Technology Parks of India

(STPI)—STPI (www.stpi.soft.net), another DoE autonomous society, was

established in 1986 as part of a concentrated effort to boost export earnings

from software development and related professional services. These parks offer

a full-service “incubator” environment for entrepreneurs and small companies.

Services offered include office spaces at affordable rates, equipped with

stable electrical power supplies and international communications links. STPI

also offers a wide variety of business services and acts as a single point of

contact for companies dealing with the government. The concept was the

brainchild of Dr. N. Sheshagiri, Director-General of the National Informatics

Center, and N. Vittal, at that time the Secretary of the DoE, both of whom

serve on the National Task Force on Information Technology and Software

Development, the current effort to boost the IT sector once again.[16]

The first Software Technology Park was set up in Bangalore (STPB). Additional DoE parks were subsequently established in Bhubaneshwar, Gandhinagar, Hyderabad, the NOIDA zone near New Delhi (currently headquarters of STPI), Pune, and Trivandrum. The state governments of Rajasthan and West Bengal set up similar parks in Jaipur and Calcutta, respectively.[17] The program is currently being expanded to include Chennai, Indore, Mohali, and Mumbai, with another seven sites under consideration. The STPI as a whole is self-financing (i.e., receives no support from the Union budget), and each park is set up as an independent cost center.[18]

Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of

India (TRAI)—The TRAI (which,

like the DoT, does not have a Web site or home page) is also subordinate to the

Ministry of Communications but reports to the Parliament. It was created in

March 1997 as part of India’s effort to qualify for World Trade Organization

(WTO) membership by creating a separating regulatory body. Under the current

arrangement, the Ministry sets policy, which is implemented by the DoT, VSNL,

and other telecommunications operating companies under the supervision of the

TRAI. There has been significant contention between the TRAI and DoT over the

scope of the TRAI’s authority.

Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of

India (TRAI)—The TRAI (which,

like the DoT, does not have a Web site or home page) is also subordinate to the

Ministry of Communications but reports to the Parliament. It was created in

March 1997 as part of India’s effort to qualify for World Trade Organization

(WTO) membership by creating a separating regulatory body. Under the current

arrangement, the Ministry sets policy, which is implemented by the DoT, VSNL,

and other telecommunications operating companies under the supervision of the

TRAI. There has been significant contention between the TRAI and DoT over the

scope of the TRAI’s authority.

Videsh Sanchar Nigam Ltd. (VSNL)—VSNL (www.vsnl.net.in) is the monopoly international telecommunications service provider, having been established as a public company in 1986. A majority of the company’s shares are owned by the Government of India. VSNL had a market capitalization of Rs 98 billion (US$2.4 billion) as of the end of 1996.[19] Like MTNL, the company is subordinate to the Telecom Commission. Headquartered in Mumbai, VSNL has 12 branches with international communications gateways (Table 13). All gateways have satellite earth stations; the gateways in Chennai and Mumbai are also connected to international submarine cable systems, such as SEA-ME-WE 2 and 3 and FLAG. Although there is no branch office in Cochin, there is an additional SEA-ME-WE 3 landfall there.

|

Table 13. VSNL Gateways |

||

|

Ahmedabad |

Dehradun |

Kanpur |

|

Arvi |

Ernakulam |

Mumbai |

|

Bangalore |

Hyderabad |

New Delhi |

|

Calcutta |

Jallandhar |

Pune |

|

Chennai |

|

|

It is the

only commercial ISP in India, offering public Internet access via the Gateway

Internet Access Service (GIAS) (internet.vsnl.net.in), as well as providing the

international links to the Internet for the ERNET and NICNET.

Telecommunications Regulation

All civil and commercial telecommunications in India, except for radio and

television broadcasting, fall within the purview of the Ministry of

Communications and the Telegraph Act of 1885. The Ministry exercises its

authority through the Telecom Commission, comprising a chairman and four

members to oversee services, technology, finances, and production (Figure 3).

Each of these members effectively controls the operations of one or more public

companies. Until recently, all telecommunications services were provided

exclusively by three public sector companies: VSNL, DoT, and MTNL. VSNL still

has a monopoly on international communications, although that monopoly is being

challenged. Basic domestic telecommunications are supplied principally by the

DoT and MTNL, although a second landline carrier has been licensed in each of

20 telecommunications “circles.” Mobile services—paging and cellular

telephony—are provided by licensed private companies, although MTNL is

attempting to create a cellular service in its areas of operations.

HTL ITI DoT TCIL MTNL VSNL

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 3. Composition of the Telecom Commission

(In addition to the three public-sector telecommunications operating companies, the Telecom Commission oversees the activities of the three public telecommunications sector industrial companies: Hindustan Teleprinters Ltd. (HTL), Indian Telephone Industries Ltd. (ITI), and Telecommunications Consultants of India Ltd. (TCIL). HTL manufactures mechanical and electromechanical printers, ITI manufactures switching and transmission equipment and subscriber terminals, while TCIL specializes in installation and maintenance.)

Preparations for entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) required the communications ministry to separate the regulatory and operating functions, with a view toward the eventual privatization of the services sector. As a result, the TRAI was created. Its powers are enumerated in The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act, 1997, of 28 March 1997. Although the Act gives the TRAI broad powers to make technical, operational, and licensing recommendations, and generally “facilitate competition,” there does not appear to be any clause that requires any other government agency to actually seek or comply with the TRAI’s recommendations. Further actions in preparation for WTO membership include the corporatization of the DoT[20] and eventual public sale of majority stakes in the three operating companies.

The scope of the TRAI’s powers was recently decided in a judicial dispute between the Authority and the DoT. The DoT had taken several actions in late 1997 and early 1998 that were questioned by various private sector companies and trade groups that filed formal petitions with the TRAI. On this basis, the TRAI issued orders staying DoT’s actions and requiring the DoT to first seek the TRAI’s recommendations and then comply with them. The DoT petitioned the High Court on the grounds that TRAI had exceeded its authority. In July 1998, the High Court ruled in favor of the DoT,[21] effectively undercutting the TRAI and calling into question India’s entire telecommunications regulatory regime.

The ruling cleared the way for the licensing of private Internet service providers (ISP), because the issue of DoT’s authority to establish licensing requirements for ISPs was one of the three questions at issue in the court proceeding. DoT had originally announced its general Internet licensing policy, including its intention to license an unlimited number of applicants nationwide, on 5 November 1997. The same day, MTNL announced that it was establishing a new division for the purpose of offering Internet services. The licensing specifics were announced by DoT on 15 January 1998, and applicants were invited to purchase the application forms. The following day, the E-mail and Internet Services Providers Association (EISPA) petitioned the TRAI to interdict the DoT policy, which its members thought was too restrictive. (The DoT had apparently not consulted with the Association in establishing the licensing procedures. This fact was probably more important than any questions about the actual procedures.) The TRAI heard EISPA’s petition on 19 January, and issued an order on 17 February requiring the DoT to stop selling license applications and seek TRAI’s concurrence before announcing a new Internet policy. The DoT then petitioned the High Court, seeking to reverse TRAI’s order. On 20 March 1998, the High Court declined to rule on the case, but issued an order allowing DoT to sell applications “at risk” while the Court reviewed the case, which was ultimately settled in DoT’s favor in mid-July.

Networks in India

A

Brief History

Following early developments in local and, later, wide area networks (LAN and WAN, respectively), India has made only limited progress in deploying modern digital networks, notably fiber optic backbones and IP-based networks. Despite the significant presence of Indian companies on the Worldwide Web (WWW) and the large number of Indian Internet users worldwide, the Internet has neither been well-developed nor effectively used in India. The country is poised, however, on the brink of major policy shifts that are likely, if made, to facilitate the rapid growth and diffusion of IP-based networks connected to the Internet.

The organizations currently operating IP-based networks in India with Internet connections are the ERNET India society, the National Informatics Centre, Software Technology Parks India, and Videsh Sanchar Nigam Ltd. There are a number of “legacy” networks operating in India, most of which foresee converting to IP once the regulatory environment has stabilized. Table 14 presents the time-line of networking development in India.

“Legacy”

networks and their evolution

After about ten years of developing computer awareness in the public sector and establishing the basis for computer support throughout the government and academia, the Indian government initiated three wide-area computer networking schemes in 1986/7: INDONET, initially an Systems Network Architecture (SNA) network to serve the country’s hundreds of IBM mainframe installations; NICNET, a nationwide VSAT network for public sector organizations; and ERNET, to serve the academic and research communities. VSNL also initiated several wide-area networks (WAN) during the 1980s. All of these networks now offer gateways to the Internet; most have either converted to the Internet Protocol suite or are in the process of conversion.

INDONET—CMC Limited (www.cmcltd.com) was established in October 1976 as the Computer Maintenance Corporation Limited, a Government of India enterprise, for the purpose of taking over responsibility for maintenance of approximately 800 IBM India installations throughout the country. IBM India announced its decision to retire from the Indian market in November 1977,[22] its assets having been effectively nationalized under the emergency powers invoked by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (the “IBM Go Back” initiative).[23]

Initially set up to maintain and operate IBM mainframe installations, CMC branched out into the areas of computer education, software development, and turn-key projects in 1984. The company established the country’s first nationwide SNA network, INDONET, in 1986, using lines leased from the Department of Telecommunications (DoT), the government’s local and domestic long-distance (STD) telecommunications monopoly.[24] The network was subsequently up-graded to the X.25 packet-switching protocol.[25]

|

Table 14. Indian Networking Time-Line |

|

|

March 1975 - |

- NIC

established |

|

October 1976 - |

- Computer

Maintenance Company (CMC) established |

|

|

|

|

1978 - |

- CMC

takes over former IBM India maintenance operations |

|

|

|

|

1980 - |

- NCST

developed/deployed proprietary e-mail software for LANs |

|

|

|

|

1982 - |

- NCST established indigenous, proprietary VSAT[26]

network - Experimental 32 Kbps packet-switched network,

COMNEX, connected Ahmedabad, Mumbai, and New Delhi. |

|

|

|

|

1986 - |

- INDONET

X.25 network commissioned by CMC ERNET

project initiated |

|

|

NCST

established first inter-campus e-mail link (NCST to IITB[27]) |

|

1987 - |

- NICNET

(first nationwide VSAT network) established |

|

|

District

Information System (DISNIC) program established by NIC |

|

1988 - |

-

NCST established first

e-mail link with the USA VSNL

commissioned Gateway Packet Switching System |

|

1989 - |

- NCST

connected to I-NET/X.25 via dial-up connection |

|

|

NCST

connected ERNET to the Internet via UUNet Technologies |

|

|

IndiaLink

established to serve regional NGOs[28] |

|

May 1989 - |

- NCST

registered as the .in domain

manager |

|

1990 - |

- NCST

established leased line to I-NET |

|

1991 - |

- VSNL

introduced Gateway Electronic Mail Service Election

results disseminated in near real-time via NICNET |

|

1992 - |

- VSNL

introduced 64 Kbps leased line service NCST

up-graded I-NET leased line to 64 Kbps[29] |

|

1993 - |

- VSNL

introduced EDI services |

|

|

|

|

August 1995 - |

- VSNL

started offering commercial Internet access[30] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

April 1998 - |

- ERNET reconstituted as an independent

“society” |

Today,

INDONET connects eight cities via 64 Kbps leased lines. The entire network is

backed up by redundant links provided by VSNL’s X.25 service, I-NET. Figure 4

depicts the current network. Today, one of the main services offered by INDONET

is X.400 for electronic data interchange (EDI) and e-mail, with gateways to the

global Internet in Calcutta and Mumbai. CMC is in the process of adding

connections to Lucknow and Vizag, providing additional links via the DoT’s

High-speed VSAT Network (HVNET), and up-grading the network to TCP/IP.[31]

CMC has submitted a license application to become a commercial Internet Service

Provider (ISP).

Today,

INDONET connects eight cities via 64 Kbps leased lines. The entire network is

backed up by redundant links provided by VSNL’s X.25 service, I-NET. Figure 4

depicts the current network. Today, one of the main services offered by INDONET

is X.400 for electronic data interchange (EDI) and e-mail, with gateways to the

global Internet in Calcutta and Mumbai. CMC is in the process of adding

connections to Lucknow and Vizag, providing additional links via the DoT’s

High-speed VSAT Network (HVNET), and up-grading the network to TCP/IP.[31]

CMC has submitted a license application to become a commercial Internet Service

Provider (ISP).

NICNET—In 1987, the NIC commissioned the country’s first nationwide VSAT network, NICNET, to provide data communications for government agencies. The network links the national capital with all state and territory capitals and 440 of the country’s 531 district headquarters. The main processing center is located at NIC’s headquarters in New Delhi, and there are regional processing centers in Bhubaneshwar, Hyderabad, and Pune. NICNET’s services include e-mail, remote database access, data broadcasting, EDI, and the Emergency Communication System.[32] The network is also the backbone for proprietary government networks (“closed user groups”), such as those of the Election Commission, Steel Authority of India Ltd., Indian Farmers Fertilizer Cooperative Ltd., Nathpa Jhakri Power Corporation, Central Excise, and the Post Office.

One of NICNET’s more interesting innovations was the creation and deployment of a rural development information system targeted at illiterate farmers. The system was distributed to rural development offices on CD-ROM, and provides pictorial and oral information about government assistance programs. NIC has also integrated a geographic information system (gisd.delhi.nic.in) into its services and is establishing a nationwide land records management system.[33] Other representative NICNET services and projects are listed in Table 15.

In each district, a Systems Analyst has been appointed the District Informatics Officer. With the help of a District Informatics Assistant, he functions as the “ADP department” for the district. These personnel account for approximately one-third of the NIC’s staff.[34] The NIC and NICNET are funded by involuntary contributions from each state and district’s budget. These contributions amount to 2-3 percent of each administration’s budget and are levied in lieu of each organization having its own ADP budget and organization. NIC’s annual budget is approximately Rs 140,000 crore (US$34.5 billion).[35]

|

Table 15. Representative NIC/NICNET Projects and Services[36] |

|

|

Central Budget processing |

Computerized Rural Information Systems Project

(CRISP) |

|

Regional Passport Office |

Fertilizer Distribution |

|

Small Scale Industries Census |

Treasury Accounting |

|

Census 1991 |

State Bank of Travancore |

|

Central Excise Computerization Project |

Court-NIC |

|

Patent Information Services |

Computer-Aided Paperless Examination System (CAPES) |

|

Biomedical Information Services |

District Information System (DISNIC) Program |

|

General Information Service Terminal (GISTNIC) |

ADONIS Bibliographic Information Services |

|

Teletext

Application Systems: Indian Airlines,

Air India, Press Trust of India, Northern Railway, Over-the-Counter

Stock Exchange |

|

The network was originally commissioned using the X.25 packet-switching protocol, and C-band VSAT links remain X.25, although some organizations run IP over the X.25 portion of the network. Ku-band satellite links use IP.[37] The master earth station, in New Delhi, uses an Equatorial MC-200 13m antenna for C-band communications via INSAT 1-D (E). The master earth station transmits multiple 5 MHz-wide, 153.6 Kbps data streams. Code-Division Multiple Access (CDMA) technology is used to maximize the network’s efficiency. The network’s 450 remote earth stations use 1.8m dishes, up-linking data at 1200 or 9600 bps and receiving a 19.2 Kbps down-link.[38]

NIC is up-grading the network to the “NICNET Info Highway,” a Ku-band overlay network which provides 1 Mbps data communications via single-channel per carrier (SCPC) satellite links. These links are being established to 70 “economically and commercially important cities/towns,” and can be further up-graded to 2 Mbps. Local area networks connected to this service use 2 Mbps wireless communications. The 7m hub earth station is collocated with the C-band antenna in New Delhi. Remote sites, of which there currently are about 400, use 1.8m or 2.4m antennas.[39]

Also operating in the Ku-band is a government video-conferencing network that connects 25 centers to support the Chief Ministers of the states, the Prime Minister’s office, and the various Union ministries. The service uses a single 72 MHz transponder.

Although the NIC favors the X.400 protocol due to its inherent security features, there have been problems interconnecting individual X.400 networks to provide wider connectivity, and the NIC believes that the Internet (i.e., IP protocol networks) provide the most cost-effective basis for a national information system. One candidate for development into a universal access data network is the Post Office’s computer network, which currently handles only back-office operations. The network could be expanded to handle individual communications because the Post Office already has a nationwide network of facilities with trained staff and electricity and a robust infrastructure. And, people are used to relying on the Post Office for written communications (e.g., mail, telex).[40]

One of the applications that is being converted to an IP network using Web (browser) and SMTP (e-mail) access is EDI, because establishing and maintaining closed business user groups, termed “communities,” over an IP network is less expensive and easier to interconnect than using proprietary EDI software. The most significant problem being faced in the course of this conversion process is encryption. Currently, NICNET relies on the Secure Socket Layer 2 (SSL2) standard for encrypting sensitive data using approximately 200 server certificates. Given the insecurity of SSL2, NICNET would like to up-grade to SSL3. However, they estimate that they would require millions of certificates, and there is no certifying authority in India. NIC has therefore proposed that it be established as a certifying authority for Indian servers. In the mean time, the bulk of sensitive data, principally financial transactions, will continue to be transmitted over the X.400 network using proprietary encryption techniques.[41]

VSNL Networks—Since Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited (www.vsnl.net.in) is licensed only for international telecommunications, all of its network offerings are prefixed with the title “Gateway,” regardless of whether the subscriber uses them for international or domestic communications. In theory, VSNL only offers gateways to other countries, not domestic services.

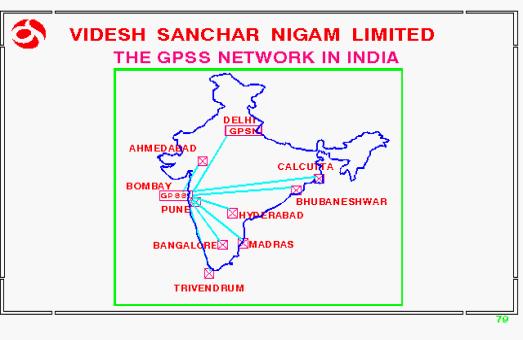

VSNL operates the Global Packet-Switched Service (GPSS), an international packet-switched service using the X.75 protocol at speeds up to 64 Kbps.[42] The GPSS network comprises three Packet Switching Exchanges (PSE) in Mumbai, New Delhi, and Calcutta, with high-speed interconnections as depicted in Figure 5, and packet assembler-disassembler switches in Bangalore, Chennai, Trivandrum, and at the Software Technology Parks (STP) in Bhubaneshwar and Pune. The network supports the ITU-T X.3, X.28, X.29, X.25, X.75 and X.121 protocols. The GPSS can be accessed directly via dial-up (X.28) or leased lines, or via links to DoT’s data networks. It provides connections to most foreign packet-switched networks. There is also a gateway to the Internet, supporting text communications (i.e., shell access).

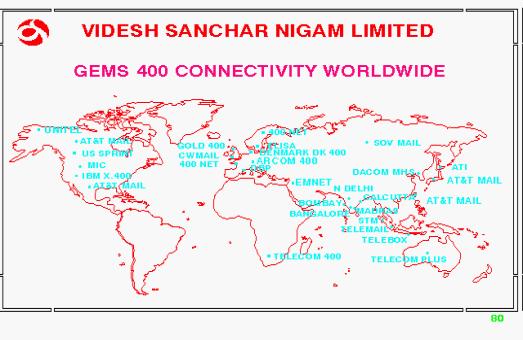

The Gateway Electronic Mail Service (GEMS 400) is an X.400 international e-mail network. The GEMS Message Handling System has nodes in Bangalore, Calcutta, Chennai, Mumbai, New Delhi, and Pune. Subscriber access is via local dial-up in those six cities and via I-NET from elsewhere in the country. There is an e-mail gateway between GEMS and the Internet. GEMS can also be used to send Telex messages and facsimiles.[43] Figure 6 depicts the system’s direct connections.

VSNL offers international EDI services via its Gateway Electronic Data Interchange System (GEDIS), or GEDIS Trade*Net. GEDIS uses industry-standard INSTRADANET software to provide secure data communications using the EDIFACT (EDI for Administration, Commerce, and Transport), UN Trade Data Interchange (UNTDI), and ANSI X.12 standards. GEDIS nodes are located in the same six cities as GEMS. Direct international connections are available to MCI, AT&T, and Sprint EDI networks, Singapore Network Services, and General Electric Information Services.[44]

Figure 5. The GPSS Network Infrastructure

VSNL also markets Concert plc.’s Concert Packet Services in India. Concert is an international consortium centered on BT (formerly British Telecom). Access nodes supporting X.25 ASYNCH and SDLC, BSC, SNA, and SDLC are located in Bangalore, Calcutta, Chennai, Mumbai, and New Delhi.[45]

More recently, VSNL signed a national data carrier agreement to market Global One services, including Global Frame Relay, Global LAN-to-LAN, and Global X.25, in India. Managed network nodes were established in Bangalore, Mumbai, and New Delhi, providing high speed connections to Global One’s 1,400 points of presence worldwide.[46] Global One is a joint venture of Sprint, Deutsche Telekom, and France Telecom.

DoT Networks—The DoT offers domestic satellite communications services through the High-speed VSAT Network (HVNET), as well as nationwide packet-switched services via the India Network (I-NET). Remote access for data communications is provided by the Remote Area Business Message Network (RABMN).

Figure 6. GEMS International Connectivity

The I-NET packet-switched public data network (PSPDN) uses the X.25 protocol and has nodes in eight cities: Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Calcutta, Chennai, Hyderabad, Mumbai, New Delhi, and Pune. Connections to GPSS are available in Bangalore, Calcutta, Chennai, Mumbai, New Delhi, and Pune. There is also a gateway to the Internet which is designed to handle primarily e-mail and text communications (i.e., shell access).

In early 1998, the DoT announced a new category of private network, Broad User Group (BUG) Data Networks. BUG Data Networks are essentially virtual private networks created through the interconnection of two or more private networks. A BUG can be set up on the basis of INET or leased line access from the DoT. One of the first organizations to take advantage of this new network category was SITA (Société International de Télécommunications Aéronautique), an international cooperative that operates a global network primarily serving the air travel industry.[47] SITA has been offering public networking services on a commercial basis since 1995.

The RABMN is interconnected to the GPSS network at Mumbai. It is also possible to access the Internet via the RADMN for text communications.

E-Mail Certain value-added services, including e-mail and the operation of private networks, were liberalized in 1995. There were eleven non-Internet-based e-mail service providers (Table 16) and 13 closed user group (CUG) VSAT network operators in India (Table 17) as of late 1995. An additional five VSAT network proposals pending at that time.[48]

|

Table 16. E-Mail Services Licensees |

||

|

Archana Telecommunication Service. |

Global Telecom Service Ltd. |

Swift Mail Communications Ltd. |

|

CMC Ltd. |

C.G. Graphnet Pvt. Ltd. |

VSNL |

|

Dataline & Research Technology |

ICNET Pvt. Ltd. |

Wipro BT Telecom Ltd. |

|

Datapro Information Technology |

Sprint RPG |

|

|

Table 17. Closed User Group VSAT Network Operators |

||

|

Amadeus Investments & Finance |

Hughes Escorts Communications |

Rama Associate |

|

Comsat Max |

ITI |

RPG Satellite Communications |

|

Dataline & Research Technologies (I) |

MARCSAT Communications |

SATNET Communications |

|

HCL Comnet Systems and Services |

Punjab Wireless & Systems |

Wipro |

|

Himachal Futuristic Communications |

|

|

ERNET brings the Internet

The Education and Research Network (ERNET) was established by the DoE in 1986 as a multi-protocol network with seven other government organizations: NCST; the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore; and five IITs, in Chennai (Madras), Kanpur, Kharagpur, Mumbai, and New Delhi. The project received technical and financial support from the UN Development Program (UNDP). ERNET initially handled TCP/IP and OSI-IP traffic, but was converted to all-TCP/IP in 1995. The goals of the project were to set up a nationwide computer network for the academic and research communities, conduct research and development in computer networking, and provide networking training and consulting services.[49]

During its first two years, the ERNET project was engaged in planning the development of a nationwide academic network and evaluating software and hardware systems. The Unix operating system was selected as the basis for the network because it was inexpensive, most of the existing Internet software was supported, and technical assistance was widely available.[50] During this time, NCST established the first inter-city (with Bangalore) and international (with the United States) electronic mail (e-mail) links, in 1987 and 1989, respectively.

The first connection to the global Internet, a 9.6 Kbps UUCP link between NCST and UUNet Technologies in the United States, was established in February 1989. It was up-graded to a 9.6 Kbps leased line and full TCP/IP connectivity by the end of 1989. NCST’s domestic connection at that time comprised a dial-up link with VSNL’s I-NET X.25 packet-switched network, later up-graded to 9.6 Kbps leased lines connecting Bangalore, Chennai, Mumbai, and New Delhi. Access was via Trailblazer modems which were capable of supporting 9.6 Kbps links only with other Trailblazers; connections with other types of modems were usually at 2,400 bps.[51] The international link was up-graded to 64 Kbps in 1992. The terrestrial network was later augmented by a VSAT satellite network deployed by ERNET in 1994.[52]

Largely because it established the first domestic Indian node on the Internet, the NCST was designated the .in national top-level domain (TLD) manager.

Status

of the Internet

Estimates vary greatly, but it is apparent that the Internet is widely used in India. According to Dr. S. Ramani, the Director of NCST, there are a total of about 312,000 “Web-level” users,[53] but other estimates run as high as 400,000 users.[54] There is also a large but undetermined number of electronic mail users without full Internet connectivity. There are about 1,000 Indian companies with off-shore Web sites in addition to the domains/servers located in India.[55] Table 18 shows the approximate growth of the .in domain over the past six years.

|

Table 18. Growth of the .in Top-Level Domain[56] |

|

|||||

|

Date |

Commercial Subscribers |

Domains |

Hosts |

Annual Host Growth Rate |

|

|

July 1992 |

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

January 1993 |

|

|

79 |

1,217

% |

|

|

July 1993 |

|

|

110 |

39

% |

|

|

January 1994 |

|

|

138 |

25

% |

|

|

July 1994 |

|

|

316 |

129

% |

|

|

January 1995 |

|

27 |

359 |

14

% |

|

|

July 1995 |

|

36 |

645 |

80

% |

|

|

January 1996 |

|

16 |

788 |

22

% |

|

|

March 1996 |

10,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

July 1996 |

|

96 |

2,176 |

176

% |

|

|

January 1997 |

|

148 |

3,138 |

44

% |

|

|

March 1997 |

24,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

July 1997 |

|

228 |

4,794 |

53

% |

|

|

January 1998 |

|

|

7,175 |

50

% |

|

|

May 1998 |

107,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

July 1998 |

|

500-600 |

10,436 |

45

% |

|

ERNET

Today, the ERNET’s infrastructure comprises landlines within metropolitan areas and VSAT links between cities. The network comprises eight “backbone sites” (Table 19) and 104 VSATs (Table 20), based on Hughes Network System (HNS) technology. The network hub, located in New Delhi, can maintain communications with each of five VSAT remote sites on each of 24 outbound channels. The total up-link bandwidth at the hub is 512 Kbps. The inbound links from the VSATs are time-division multiplexed into groups of 10 stations operating at an aggregate bandwidth of 128 Kbps. The system uses an INSAT-1D[57] 22 dBW C-band transponder that supports one outbound link and 11 simultaneous inbound (VSAT to hub) links. The network uses the X.25 protocol as the carrier for TCP/IP traffic. The X.25 carrier is required because the VSAT network’s space segment uses a proprietary HNS protocol incompatible with TCP/IP.[58] There are seven connections to the Internet via VSNL international gateways, of which five operate at 2 Mbps (Table 21). The ERNET supports approximately 80,000 users at 700 organizations, carrying more than 10 GB of traffic daily.[59] Approximately 12,000 ERNET subscribers are “serious” users who log on every day and use the Internet extensively. There are an additional 20,000 who use e-mail only.[60]

|

Table 19. ERNET Backbone Sites[61] |

|

Department of Electronics (DoE), New Delhi (Delhi) |

|

National Centre for Software Technology (NCST), Juhu, Mumbai (Maharashtra) |

|

Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore (Karnataka) |

|

Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IITM), Chennai (Tamil Nadu) |

|

Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA), Pune (Maharashtra) |

|

Variable energy Cyclotron Center (VECC), Calcutta (West Bengal) |

|

Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur (Uttar Pradesh) |

|

Central University, Hyderabad |

In April 1998, the group of people who established and were running the ERNET successfully lobbied the government to establish “ERNET India” as an “autonomous society” under the Department of Electronics. Table 22 lists the Governing Council of ERNET India. In June 1998, ERNET India became a member of the Internet Society (ISOC) in the start-up category.[62]

|

Table 20. Principal ERNET VSAT Nodes[63] |

|||

|

Location |

Number of Terminals |

Location |

Number of Terminals |

|

Ahmedabad |

2 |

Kodai Kanal |

1 |

|

Allahabad |

1 |

Kurukshetra |

1 |

|

Anand |

1 |

Madras |

2 |

|

Bangalore |

2 |

Mumbai |

4 |

|

Baroda |

1 |

Mussoorie |

1 |

|

Bhubaneswar |

1 |

Mysore |

1 |

|

Calcutta |

1 |

New Delhi |

3 |

|

Calicut |

1 |

Patiala |

1 |

|

Chandigarh |

1 |

Pilani |

1 |

|

Coimbatore |

1 |

Pondicherry |

1 |

|

Gandhinagar |

1 |

Pune |

1 |

|

Gauribidanur |

1 |

Roorkee |

1 |

|

Goa |

1 |

Surat |

1 |

|

Guwahati |

1 |

Surathkal |

1 |

|

Hyderabad |

1 |

Tiruchirapally |

1 |

|

Indore |

1 |

Udaipur |

1 |

|

Kalpakkam |

1 |

Vijayawada |

1 |

|

Kanpur |

1 |

Warangal |

1 |

|

Kharagpur |

1 |

|

|

|

Table 21. ERNET Gateways to the Internet[64] |

|

|

Location |

Speed |

|

DoE, New Delhi (Delhi) |

2 Mbps |

|

Software Technology Park, Bangalore (Karnataka) |

2 Mbps |

|

VECC, Calcutta (West Bengal) |

2 Mbps |

|

NCST, Juhu, Mumbai (Maharashtra) |

64 Kbps |

|

NCST A-1 Building, Mumbai (Maharashtra) |

256 Kbps |

|

IUCAA, Pune, (Maharashtra) |

2 Mbps |

|

IITM, Chennai (Tamil Nadu) |

2 Mbps |

Other groups with a similar legal status include the NCST, Centre for Development of Telematics (C-DOT), Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (C-DAC), and Software Technology Parks of India (STPI).

This moves ERNET out of the Information Infrastructure Division of the DoE, and coincidentally establishes it as an independent budget center. Although the Society has been officially established, it is still in the organization phase. Finances, operating principals, offices (they have been asked to vacate their spaces in the DoE headquarters building), and staffing are all being worked out. The 30-40 DoE employees who are currently attached to ERNET will be given the opportunity to transfer to Society employment, although few are expected to do so because they would have to relinquish their civil service benefits.[65]

|

Table 22. The Governing Council of ERNET India[66] |

|

|

Chairman |

Minister of State for Electronics |

|

Chairman (Alternate) |

Minister of State for Science and Technology |

|

Vice-Chairman |

Secretary, Department of Electronics |

|

Members |

Secretary, Department of Science and Technology |

|

|

Science Advisor to the Defense Minister and Secretary,

Department of Defense Research and Development |

|

|

Secretary, Department of Scientific and Industrial

Research |

|

|

Secretary, Department of Space |

|

|

Secretary, Department of Atomic Energy |

|

|

Finance Secretary |

|

|

Secretary, Department of Education |

|

|

Chairman, Telecom Commission |

|

|

(one of the Directors of an Indian Institute of

Technology) |

|

|

Director, Indian Institute of Science |

|

|

Executive Director, ERNET India |

|

|

(“two experts in the area of computer networking”) |

|

|

(“two persons from the industry/user community”) |

Money was the main issue behind the creation of the ERNET India society. ERNET was originally funded by the UNDP, with some additional funding from the Union government, but the UNDP funding ran out in 1995, by which time the UNDP’s Terminal Evaluation Team had recommended that ERNET be set up as an autonomous body. ERNET has been limping along for the past two years on a “bridging” grant from the Union government while people decided what to do with it. As of last year, it even looked as if ERNET might be shut down. ERNET is theoretically to be supported by its customers, but it is nowhere near being self-sufficient today.

Although ERNET’s existing subscribers do not pay for the service, ERNET hopes to become financially self-supporting by attracting new, paying subscribers and offering additional services to existing subscribers, for a fee. The nation’s 8,000 colleges and primary and secondary schools are viewed as ERNET’s natural market, which is virtually untapped. ERNET also intends to compete with NIC for business from commercial and government research laboratories, where ERNET has an early lead. They also intend to market ERNET services to government branches and departments, currently NIC’s almost exclusive domain (with the exception of ERNET’s sponsor, the Department of Electronics). ERNET’s strategy in this regard is to price its services lower than those of any other ISP, which will “automatically” win it government contracts, which are obliged to go to the lowest bidder. Finally, ERNET intends to market its services to non-government organizations (NGO) and individuals.[67] Table 23 is the proposed fee structure for ERNET Internet services.

|

Table 23. Proposed ERNET Internet Fees[68] |

|

|

Service |

Annual Fees |

|

Unlimited dial-up |

Rs 10,000 (US$246) |

|

Additional mail box (e-mail address) |

Rs 5,000 (US$123) |

|

Analog leased line |

Rs 110,000 (US$2,700) |

|

64 Kbps leased line |

Rs 310,000 (US$7,635) |

|

2 Mbps leased line |

Rs 2,510,000 (US$61,823) |

|

Wireless link |

Rs 510,000 (US$12,562) |

While ERNET pioneered the Internet in India, it is not clear that it will survive much longer. Despite its new status as a Society, as noted above, serious budget and personnel issues remain to be resolved. The Indian government has allocated only minimal funding to ERNET since its inception; most of the network development was funded by the UNDP. Today, it is expected to operate on a commercial basis when none of its existing clients pay for the services. In September 1998, the ERNET society was dealt another blow when the founder and most vocal supporter of ERNET, Dr. Ramakrishnan, was relieved as Executive Director of ERNET India by the newly-appointed Secretary of the DoE, Ravindra Gupta. The society’s new Executive Director is Gulshan Rai, who is not well-known in the networking community. The prospects for the survival of ERNET appear to be at their bleakest ever. Should the society be shut down, it is possible that the NIC might absorb ERNET’s assets and keep the network operating, although this is likely to be accompanied by some serious political in-fighting, as the NIC does not fall under DoE’s purview. Even though the DoE does not appear enthusiastic about the ERNET, it will probably not give away the assets willingly.

NCST

Although an independent agency with its own unique mission, the National Centre for Software Technology (NCST) has played a critical role in the development of the Internet in India. NCST was the first institution in India to establish an international connection to the Internet, and acquired along with the connection the responsibility for managing the .in national TLD, since they established a root-server and the first .in domain (ncst.ernet.in). During subsequent government reviews, NCST’s management of the TLD has not been questioned.

NCST does not charge for registering domains under the .in TLD, but only about 400 domains were registered as of June 1998. This is partly due to the strict conditions that NCST puts on the assignment of domain names. In order to register a particular name, the applicant must produce either a company registration form or trademark registration that proves that the company is entitled to use the name for which it is applying. The NCST’s reasoning is that domain names “apparently” have commercial value, so NCST should attempt to adhere to such Indian law as might be seen to apply (i.e., trademark law).[69] A possibly unintended result of this policy is that companies wishing to register snappy names, such as indiagate, indiaweb, etc., wind up having to go offshore—to InterNIC—since their companies don't “own” those names. This policy has raised the hackles of the Internet community in India, which believes companies should be able to pay a nominal fee and register any unclaimed domain name.

NCST also does not activate domain names just to keep others from using them. For example, when VSNL set up a subsidiary called VSSL to handle its Internet business, it wanted to do business under the vssl.net.in name, but also wanted to register vssl.co.in to prevent anyone else from using it. NCST registered both names, but did not assign the .co domain an IP number/block or publish its registration. That is, the name is now blocked out in NCST's database, but not a “registered” domain name. While NCST is being very parsimonious with its IP address space for no apparent reason, on the other hand, it is “not selling fake real estate.”[70]

NCST is currently consulting on the establishment of a nationwide banking network under the aegis of the Institute for Development and Research of Banking Technology (IDRBT), on the governing council of which NCST has a seat. This network will be centered on a Hughes Network Systems (HNS) hub in Hyderabad that will be available to all of the country’s 105 banks, although only a few of the majors have committed to using the system.

NICNET

As previously noted, parts of NICNET currently use IP, and NIC is expanding its Web-based service offerings. Since 1995, NICNET has offered Internet access via VSNL gateways in the four “metros” (Calcutta, Chennai, Mumbai, and New Delhi) and Bangalore and Pune.[71] The NIC also maintains Web pages for its government clients. By early 1998, high-speed Internet access was available throughout the network through the use of one of three new VSAT types: FTDMA,[72] DirecPC, and IP Advantage. The FTDMA and DirecPC earth stations are receive-only; outbound communication to the Internet are carried on normal telephone circuits. IP Advantange is a full duplex satellite communications system using Integrated Satellite Business Network (ISBN) protocols at 64 Kpbs (subscriber-to-hub) and 512 Kbps (hub-to-subscriber). The ISBN hub is located at NIC’s headquarters in New Delhi.[73] NIC is offering new subscribers Hughes Network Systems “DirecPC” earth stations for Rs 90,000 (US$2200); service costs Rs 5,000 (US$125) per year.[74] Remote stations using the C-200 VSATs have been up-graded to enable them to use the DirecPC system.[75]

NICNET does not, however, intend to become a commercial ISP, and sees the provision of Internet access as an adjunct to its service offerings. As of mid-1998, NICNET estimated that there were a total of 20,000-25,000 e-mail users on the network. Each state government maintains an SMTP server and has approximately 30 multiple-user e-mail accounts. NIC recently implemented an X.500 user directory that is accessible via the Web.[76]

The creation of Web-based EDI interfaces is seen as one of the principal growth areas for NICNET. Although these services are currently not accessible via the Internet, NIC is developing a gateway to permit companies to access NICNET’s Web-based EDI services without having a dedicated NICNET connection. The target sector for these services are exporters, who will be able to conduct transactions with the automated ports and Customs systems via e-mail (and later, Web) interfaces for Rs 500 per month, significantly less expensive than a NICNET EDI account and with no software investment and minimal training.[77]

NIC established its first Web-based information system in early 1998, an export database of agricultural and processed food products developed for the Agricultural and Processed Food Export Development Authority of the Ministry of Commerce. The system provides summary information, database access, and a directory of producers and exporters. It makes extensive use of Javascript and Java applets to display search results and animated diagrams.[78] Eventually, NICNET intends that all public-access government databases will be accessible via a Web interface and a firewall between NICNET and the Internet. In this fashion, NIC intends to become the “one-stop shopping” center for government information.[79]

Although NIC does not intend to offer commercial Internet services, as part of its mission to provide IT services to the public sector, NIC expects to assist at least some public companies that are planning on becoming ISPs. Candidates include the railroads, electrical power utilities, and oil distribution companies, all of which are seeking additional revenues from new uses for their extensive infrastructures and rights of way. NICNET has already agreed to provide the hardware and network base for a public-access Internet service to be offered by the Northern Railroad.[80]

VSNL/DoT

VSNL’s first experience with the Internet was in the early 1990s when the then-Chairman, B.K. Syngal, was given an ERNET e-mail account.[81] On 14 August 1995, VSNL commence offering public Internet services via a gateway earth station and router in Mumbai that provided a single connection to MCI in the USA, essentially becoming an ISP. Local access nodes were installed in Calcutta, Chennai, Mumbai, and New Delhi, permitting connections via dial-up lines through the DoT or MTNL or an I-NET X.25 connection.[82] VSNL’s initial investment amounted to Rs 10 million (US$246,000) for a Web server and Rs 120 million (US$2.96 million) for routers, e-mail and access servers, and other equipment.[83]

Although no ISPs were licensed, VSNL characterized the service as a “gateway” service—Gateway Internet Access Service (GIAS)—that VSNL was allowed to provide under the terms of its license to operate international telecommunications systems. Only four months after VSNL’s Internet service was commissioned, the Indian government announced that VSNL would not have a monopoly on public Internet service provision, but that commercial ISPs would be licensed. However, VSNL was to have the exclusive right to connect these ISPs to the Internet internationally.[84]

Since then, VSNL has added five more international gateways (Figure 7) and increased the number of local access nodes to 11 (including the gateways). Five additional satellite gateways are to be established in the near future.[85] VSNL also established GIAS nodes at 19 additional locations and turned them over to the DoT for operation and maintenance. DoT also owns and operates the domestic IP network, which is carried over multi-purpose lines. Nodes in operation as of July 1998 are listed in Table 24. An additional 23 nodes are scheduled to be brought on-line by the end of 1998 (Table 25). Access is via dial-up lines at speeds up to 33.6 Kbps, 9.6 Kbps-2 Mbps leased lines, dial-up Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN),[86] or other VSNL or DoT data networks.[87]

|

Table 24. GIAS Access Nodes, July 1998[88] |

|||

|

Nodes Operated by VSNL |

|||

|

Ahmedabad |

Chennai |

Mumbai |

Pune |

|

Bangalore |

Dehradun[89] |

Mysore73 |

Trivandrum73 |

|

Calcutta |

Ernakulam73 |

New Delhi |

|

|

Nodes Operated by DoT[90] |

|||

|

Aurangabad |

Gwalior |

Kanpur |

Nagpur |

|

Chandigarh |

Hubli |

Kollam |

Patna |

|

Coimbatore |

Hyderabad |

Kottayam |

Pondicherry |

|

Goa |

Indore |

Lucknow |

Trichy |

|

Guwahati |

Jaipur |

Madurai |

|

Global

Internet

13 Software Technology

Parks Nationwide

![]()

![]()

![]() Multiple

64 Kbps AT&T USA

Multiple

64 Kbps AT&T USA

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() STPI Multiple

64 Kbps GEIS USA

STPI Multiple

64 Kbps GEIS USA

![]()

![]()

![]() Multiple

64 Kbps UUNet USA

Multiple

64 Kbps UUNet USA

Bangalore

![]()

![]()

![]()

2

Mbps MCI USA

![]()

![]()

![]() 2

Mbps Telecom

Italia Italy

2

Mbps Telecom

Italia Italy

Calcutta

![]()

![]()

![]()

128

Kbps KDD Japan

128

Kbps KDD Japan

![]()

![]()

![]() 512

Kbps MCI USA

512

Kbps MCI USA

Chennai

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 2

Mbps + 512 Kbps + 256 Kbps MCI USA

2

Mbps + 512 Kbps + 256 Kbps MCI USA

Mumbai

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

VSNL 2 Mbps + 2 x 64 Kbps MCI USA

![]()

![]()

![]() 2 Mbps Telecom Italia Italy

2 Mbps Telecom Italia Italy

![]()

![]()

![]() 2

Mbps Teleglobe Canada

2

Mbps Teleglobe Canada

![]()

![]() 64

Kbps Singapore

64

Kbps Singapore

New Delhi![]()

![]()

![]()

2

Mbps + 3 x 64 Kbps MCI USA

![]()

![]()

![]() 2

x 2 Mbps Telecom

Italia Italy

2

x 2 Mbps Telecom

Italia Italy

Pune

![]()

![]()

![]() 1 Mbps MCI USA

1 Mbps MCI USA