|

Introduction |

|

New media emulate old media at first. We will take a quick look at the

evolution of books set with moveable type, movies and television then turn to

teaching materials. Today’s textbooks and university programs

are by and large digital emulations of the past, but there is a lot of

experimentation going on. We will describe experiments with

modular teaching material, student-developed teaching material, peer tutoring

and very large classes. |

|

Technology with implications for

individuals, organizations and society |

|

Teaching and learning is an important

network application area with implications for organizations, individuals and

society. |

|

New media emulate predecessors movies |

|

New media often start out emulating old

media. Early movies were made by setting up a

stationary camera and filming stage plays. Shooting on location, moving cameras and

many other innovations followed, but years later some movies were still

filmed stage plays. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Assassinat_du_duc_de_guise.jpg http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0061184/ |

|

New media emulate predecessors:

television |

|

Early television shows often had

performers standing in front of a curtain or acting on sets similar to

vaudeville or stage plays. |

|

New media emulate predecessors:

books |

|

Books followed a similar pattern. In 1455, Johannes Gutenberg’s bible was the

first book printed using movable metal type. It is the distant ancestor of our

current textbooks. But, today’s textbooks would surprise

Gutenberg. The Gutenberg Bible resembled the hand

written manuscripts on which it was based. It did not have punctuation or

paragraphs. A single page was around 12 by 17.5

inches – suitable for contemplative reading in a library. The illustrations were added for beauty

and feeling, not clarification. Like the hand copied books before it, it

was a religious book. Gutenberg’s breakthrough was in

production, not format or content. |

|

Slow evolution of the book |

|

Fifty years after Gutenberg, Aldus

improved production by printing eight pages on a single sheet. This led to smaller, portable books that

could be carried or placed in a saddle bag. Aldus also introduced punctuation, like

the commas, periods and semicolons shown here, and italic type, which fit

more letters on a page. But, like Gutenberg, Aldus would be

surprised by the variety of punctuation and typography in today’s textbooks

as well as innovations like chapters, callouts, indices, tables, diagrams,

tables of contents and images with captions. |

|

Digital textbooks emulate print

textbooks |

|

Textbooks today are at the “Gutenberg

bible” stage. Textbook publishers have digitized their

books, making them available online in various formats. Many maintain the notion of a book-sized

page and often preserve the page numbering of the print version. These e-books look better than PDF

documents, but they are constrained by the previous format. Like Aldus, they have gone somewhat

beyond their predecessor, but remain tied to the notion that the course is

contained in a book of pages. |

|

Digital classes emulate face-to-face

classes |

|

Many universities are offering online

classes, but, like the textbook publishers, they are emulating the past. They typically offer the

"same" courses online as they teach in the classroom. They use the same textbook and ancillary

material, but use course management systems to substitute threaded discussion

or some other social media tool for in-class discussion and administer

conventional assignments and tests. |

|

Digital lectures emulate

face-to-face lectures |

|

Schools also repurpose old courses by

making video recordings of lectures with slides. But, like books, movies, television and

other media, textbooks and classes will change. It is too soon for me to predict the

future of teaching and teaching material, but I don’t think it will center on

digital textbooks, learning management systems and recorded lectures. Publishers and schools will resist it,

but changes in education will come faster than with previous media because of

the low cost of experimentation and innovation on the Internet. Let’s look at a few examples –

experiments with modular teaching material, student-developed teaching

material, peer tutoring and very large classes. |

|

Examples of collections of

independent modules |

|

Here are three modular courseware

examples. The California State University system

established the Merlot portal for modular teaching material in 1997, and

today it contains nearly 34,000 peer reviewed modules in 23 disciplines. Commoncraft and TED Ed produce short educational videos. Each is on a single topic and most are

under five minutes long. These are collections of independent

modules, but a course can also be constructed modularly. |

|

A collection of modules for a single

course |

|

Nature publishing offers a modular

Principles of Biology course, that was developed in conjunction with the CSU. There are 196 modules and a professor selects

the ones he or she wants to include in the “textbook” for their class. I put “textbook” in quotes because it is

neither a text nor a book. Each module is a scrolling multimedia

Web page with embedded quizzes. Nature’s business model is also innovative. They plan to continuously update the

material, and the student purchases a lifetime access subscription rather

than a one-time book. |

|

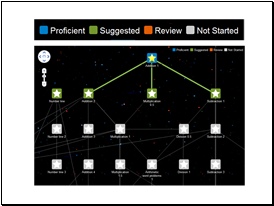

Hierarchically organized modules |

|

The Kahn Academy has over 3,000 short

videos on a variety of topics along with system for administering quiz

questions and tracking student progress. A user can jump directly to any video,

but they are organized hierarchically. For example, there are 11 Arithmetic

and Pre-Algebra topics. The first of those 11 topics, Addition

and Subtraction, is shown here. The Addition and Subtraction

topic consists of 16 video lessons. In this example, the student has

demonstrated proficiency in the Addition 1 lesson (blue), and is

prepared to go on to one of four subsequent lessons (green). He or she demonstrated proficiency by

answering several questions correctly. |

|

Modules created by students |

|

Many people are experimenting with

student generated teaching material. For example, in Georgia Tech’s Techburst

project, students create educational videos on topics of their choosing. Tech awards prizes to the best videos. Since tools for creating student

generated material are cheap and easy to use, faculty at virtually every

university are encouraging students to produce teaching material. For example, students in a Drake

University journalism class produced reviews of 20 Twitter tools. In this project, the students learned

about the Twitter ecosystem and also created something of value to others. There is a proverb that “to teach is to

learn twice,” and that is certainly true. A person making teaching material for a

skill or concept will learn it very well. |

|

Peer teaching and student

collaboration |

|

There is a lot of positive research on

peer teaching -- both the tutor and tutee benefit. Many faculty encourage peer teaching and

it is institutionalized at some universities. Take for example the peer tutoring

program at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell To be a peer tutor for a class, a

student must have a letter of recommendation from the professor, a grade of

B+ or better in the class and an overall GPA of 3.0. Peer tutors can be available during

online office hours or using asynchronous communication tools. Conversationexchange.com provides

another example. To learn or practice foreign languages,

people pair up for conversation, chat or email. Nature and other publishers are

establishing mechanisms whereby students in classes that use their material

can collaborate with and help each other, regardless of where they go to

school. The CSU is planning a similar program to

encourage communication and collaboration among students taking a given class

on any campus in the system. |

|

Very large online courses |

|

Others are experimenting with very large

classes. The largest to date so were three

Stanford computer science classes offered in the fall of 2011. The largest had 160,000 students, and

its instructor, Sebastian Thrun (shown on the right), is now offering courses

through an educational startup, Udacity.com. The Stanford/Udacity model is

interactive. The student watches a short video

presentation by the instructor, takes a short quiz, then continues. There are homework assignments and exams

as well. |

|

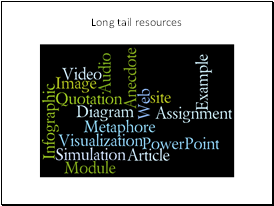

Types of teaching material |

|

Most of the teaching material we have

discussed has been video or interactive video, but modular teaching resources

come in many forms. Something as small as a quotation, image

or diagram that helps students acquire a concept can be a useful resource. The Internet is an ideal medium for such

highly focused material since the marginal cost of adding an item to a

collection is essentially zero. Amazon capitalized on this from the

start, recognizing that perhaps 100 best-selling books would account for half

their revenue while the other half would come from sales of many thousand

books, which sold few copies. Similarly, the cost of storing a diagram

that effectively illustrates a specific concept that is only taught in a

single course is essentially zero. While storage cheap, organizing and

indexing material so effective resources are easily discovered is difficult. This fine-grained modularity also makes

it easy for a teacher to improve a resource or add a new one. As with Wikipedia, a contributor can

focus on a single topic without concern for the overall collection. |

|

What are the implications? |

|

The Internet has cause disruption in the

music, book, newspaper, magazine, movie and television industries. The textbook industry is already

changing with the introduction of electronic texts, textbook rentals, online

access and so forth. Are universities next? What will happen if massive classes with

hundreds of thousands of students turn out to be good alternatives for, say,

half of the undergraduate curriculum? Will schools that focus on teaching survive? Will universities be able to fund

research? Will a better educated work force

improve the overall economy? |

|

Summary |

|

New media typically begin by mimicking

old media. Books, movies and television provide

examples of that. Textbook publishers and universities are

doing the same – using digital technology to emulate old materials and

methods. But, the low cost and ubiquity of the

Internet assure us that new materials and methods will be invented. We still do not know what they will be,

but millions of professors and companies are experimenting with digital tools

and techniques. We surveyed some of these experiments

with modular teaching material, student-generated teaching material, peer

teaching and very large classes. We also noted that Internet based

teaching material could take many forms and be tightly focused. We concluded with a few questions about

the possible impact of all this on the university, but are not yet ready to

provide any answers. |

Self-study questions

1. Find a Merlot module

that is relevant to a course you are currently taking. Write a brief description of the module and

state whether it would be helpful to you?

If so, show it to your professor.

2. Find a Kahn Academy

module that is relevant to a course you are taking or took in the past. Write a brief description of the module and

state whether it would be helpful to you?

If so, show it to the professor.

3. Would you be willing

to pay $49 for a lifetime subscription to a regularly updated textbook for any

course you have taken? Which one?

4. List the advantages

and disadvantages of Nature’s electronic text compared to a traditional biology

textbook.

5. List the advantages

and disadvantages of Nature’s electronic text compared to an electronic version

of a traditional biology textbook.

6. What will be the

implications for individuals, universities and society if it turns out that

online courses with 100,000 students are effective?

Resources

•

Review of

Nature’s modular biology text: http://cis471.blogspot.com/2011/11/post-gutenberg-e-text-for-biology-101.html

•

Merlot: http://www.merlot.org

•

The Kahn

Academy: http://www.merlot.org

•

Techburst videos:

http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLA9F9FCE212B121CF

•

Techburst home: http://c21u.gatech.edu/techburst

•

A modular digital

literacy course: http://cis275topics.blogspot.com/2011/04/modular-it-literacy-course-for-internet.html

•

Digital literacy

– evolution, curriculum and a modular e-text: http://som.csudh.edu/fac/lpress/presenatations/modularbiotext.pptx

•

The legacy of

Aldus Manutius and his press: http://net.lib.byu.edu/aldine/

•

Stanford and

other massive online classes: http://cis471.blogspot.com/search/label/mooc

•

Udacity: http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2012/01/23/udacity-and-the-future-of-online-universities/

•

MIT plans: http://tech.mit.edu/V131/N60/mitx.html

•

Review and

assessment of the first Stanford classes:

http://newsletter.alt.ac.uk/2011/11/what-can-we-learn-from-stanford-university%E2%80%99s-free-online-computer-science-courses/